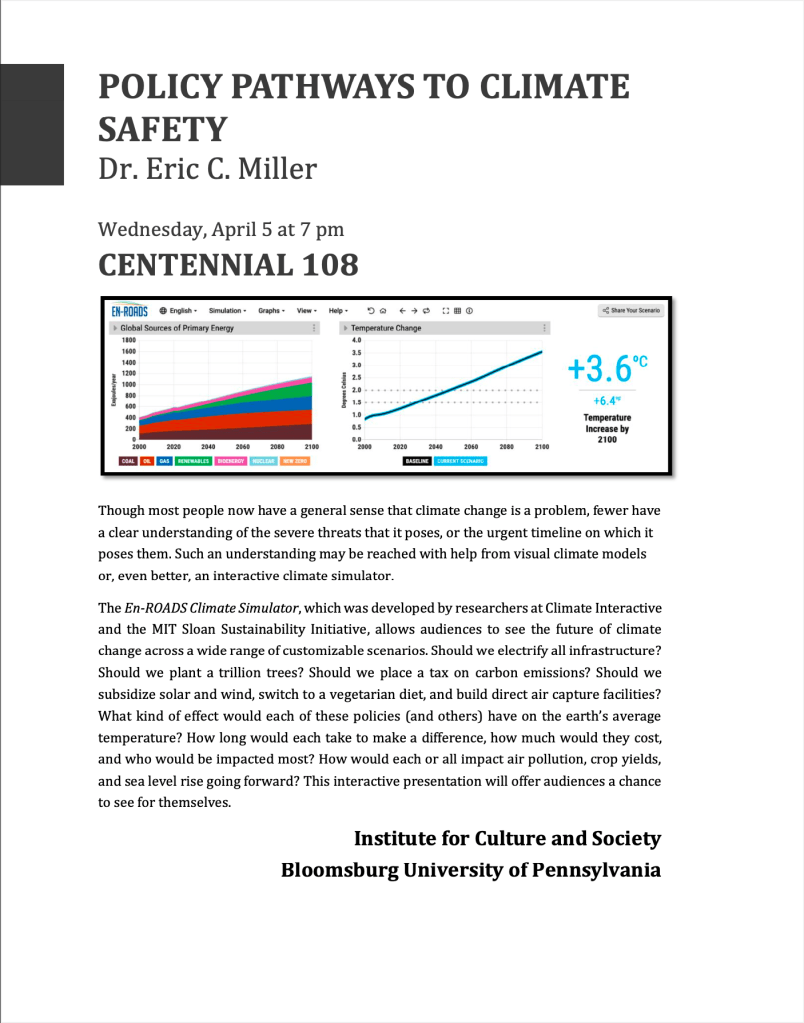

On June 1, a few days before Canadian wildfire smoke descended upon the eastern United States, engineers at MIT and Climate Interactive published an update to En-ROADS, their online global climate simulator. A clumsy acronym for “Energy Rapid Overview and Support,” En-ROADS analyzes energy demand, energy source types, and greenhouse gas emissions against policy options like fossil fuel energy, renewables, electrification, efficiency standards, and others to project global temperature increases between the years 2000 and 2100. When it was first launched in 2018, the simulator projected a global increase of 4.2 degrees Celsius within this range—a truly catastrophic figure. By 2022, Paris Agreement pledges and tech innovations had revised the projection down to 3.6 degrees—clearly better, but still bad. On June 1, it fell again to 3.3, but not for a great reason.

Among other updates, the new version of En-ROADS features an “economic damage” consideration that factors GDP losses into its projections. As climate change worsens, its effects will become more pronounced, which will impact human life and force changes in the way we operate. The resulting damage will likely cause economies to recede, which will depress energy demand, which will lower greenhouse gas emissions, which will ultimately slow the temperature rise. That this feature was introduced the same week that collapsing air quality quashed outdoor businesses up and down the eastern seaboard was coincidental, but also clarifying. We do need to reduce our emissions as quickly as possible, but we should do it intentionally and strategically, in ways that will promote clean, cheap, reliable energy supply rather than waiting for environmental crises to slashes emissions via economic damage.

This is easier said than done, of course, but En-ROADS allows us to think through our various options by mapping their effects on colorful charts within a neat, 100-year window. (For many participants, the recognition that we are on pace for catastrophic warming within the next 77 years will be a revelation in itself.) If you want to know how effective a carbon price will be at cutting fossil fuel demand and greenhouse gas emissions this century, for example, all you have to do is move the slider and the charts update automatically:

In many cases, participants learn that their preferred policy lever has less leverage than they would have assumed. There are a variety of reasons for this, including the length of time required for some policies to take effect, the tendency of some policies to crowd each other out, and the continued reliance of some policies on fossil fuels. Ultimately, though, an En-ROADS demonstration makes a few things clear. First, we need to stop burning fossil fuels as quickly as possible. The sooner we slash emissions from coal, oil, and gas, and the greater we slash them, the more stable our atmospheric future will be. Any policy that does not slash fossil fuel use in the next decade will be extremely limited in its effectiveness. Second, even the most effective levers—and a carbon fee is the single most effective lever on the board—account for only a fraction of the reductions needed to meet Paris Agreement goals. A carbon fee of $250 per ton—which is high enough to make it a political and economic non-starter—lowers the temperature projection by only one degree Celsius. To make up the difference, we have to rely on the remaining options. As the folks at Climate Interactive say, there is no silver bullet to fixing climate change. Instead, we have silver buckshot. There are a lot of policy options available to us, and we have to use all of them.

These realities become clear over a 60-90 minute interactive demonstration, in which the participants dictate the action. Anyone can raise a hand at any time, or otherwise ask that a particular lever be pulled. From this main interface, we can then click through to consider how our preferred policies affect energy costs, energy consumption, federal budgets, economic growth, global crop yields, deaths related to extreme heat, sea level rise, and other implications. Ultimately, the demonstration asks the participants to work together to create a scenario that keeps (or returns) global temperature rise to 1.5C by 2100. It’s tough—but not impossible—to do:

In my short career as a certified “En-ROADS Ambassador,” I have moderated several of these demonstrations, and have found the audiences very receptive. They tend to come away feeling both alarmed at the severity of the problem and empowered by the available means to address it. At that point, it’s up to them to get involved. If you are interested in hosting one of these events, either in-person locally or on Zoom, feel free to shoot me an email at emiller@bloomu.edu.